Meet the James Beard Award-nominee who started a local farm-to-table trend

Art Rogers is running late. It's a Wednesday at noon, and the young man who answered the door at Lento, Rogers' Village Gate restaurant, doesn't know where the owner is, but says "he'll be back; won't you have a seat?" The restaurant is eerily quiet, and a dreary mid-April sky provides the only light. Stools are stacked on each high top table in the bar area, and a large chalkboard above the bar lists the previous day's specials, including several Finger Lakes wines. In the corner, a young woman mops an already spotless floor.

Around 12:15 p.m., there's a rush of wind from the door and Rogers walks in swiftly, his bulky dark coat swishing with each movement. "Sorry about that," he says in a low tenor, his eyes apologetic behind round-rim glasses. Rogers has been in his car most of the morning, picking up fresh ingredients for the evening's pairing dinner with Black Button Distilling.

Lento, which opened in 2007, is widely considered Rochester's first farm-to-table restaurant, and Rogers' work garnered him a James Beard award nomination last year. Rogers, a Pittsford native, left home to attend the University of New Hampshire. He then worked under Chef Melissa Kelly — a two-time James Beard Foundation Best Chef: Northeast Award winner — at Primo in Rockland, Maine. The coastal restaurant maintains a 4.5-acre farm, from which most of the menu is sourced, and was farm-to-table before the term became used in culinary circles.

As the story often goes with Rochesterians, Rogers wasn't planning to return here, but in 2005 it "just sort of happened." He spent two years working at popular spots like 2Vine and JoJo Bistro, where he was head chef. But he couldn't stop thinking about his time in Maine.

"There wasn't this moment where I woke up and decided to open a restaurant," Rogers says. He moved back expecting to find something comparable to Primo, "but there was nothing even remotely close. I didn't want to take a step backward after working at a restaurant of that caliber, so I decided to try to do the farm-to-table concept. That's how I wanted to cook."

Lento was born. Rogers was barely 30 years old, and he and his wife had just started a family. It was risky, but he had a hunch the whole thing might work.

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Lento’s Art Rogers: Farm-to-table is “how I wanted to cook.”

It wasn't easy at first. He found a lot of his produce at the Rochester Public Market (which he still sources from every day it's open), and scoured the Internet to find local farmers he could approach about purchasing food for the restaurant. There was no Headwater Food Hub; there was no farm-to-table "wholesale" of any kind.

At first, the farmers weren't interested in working with Rogers. They'd tried providing to other restaurants, but due to factors like weather and crop growth, the produce needed for a menu that didn't change seasonally wasn't available. Because of his experience at Primo, Rogers had a solution.

"I went to the farms and I said, 'Hey, we're gonna change the menu based on what you have on hand. Meaning you tell me if you have heirloom tomatoes on hand,''" Rogers says. "No one had ever said that to them before." Back then, Lento menus were printed almost every day (now, it's more like two or three menus per week). And the menus were a little different, too.

Listing the names of every farm-partners on each printed menu was one of the things that first set Lento apart. Rogers was adamant about the information staying on the menus — even though family, friends, and even customers thought it was too confusing and wordy.

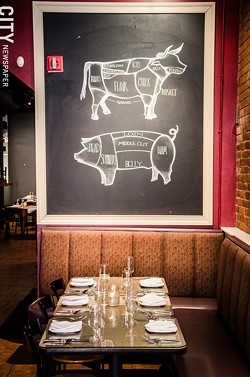

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Interior shots of Lento in Village Gate Square.

"I never swayed from that. I was like, 'That's what we do,'" he says. "You see so many restaurants that say, 'We support local,' and then you'll ask a server, 'Where does this come from?" and they don't know.'" Rogers didn't want to have a generic answer.

"If this is on here, not only are we helping to market the farm, but people know exactly that there's no BS," he says. In the wake of recent news about faux farm-to-table claims, the "no BS" commitment is refreshing. Each partner is also listed on the Lento website.

Rogers' pioneering ways caught the attention of the James Beard Foundation last year, and he became the first (and only) Rochester-area semifinalist for Best Chef: Northeast. Though he didn't win, Rogers credits the nomination for an influx of out-of-towners. "People who have their finger on the pulse of what's happening in the food world always find us," he says. "The book is filled with out-of-town, non-585 numbers most nights."

If anything, that's what Rogers would change about Lento: the lack of local diners. It's part of the reason for Wednesday pairing dinners. "Wednesdays tend to be tumbleweed nights" at Lento, he says, and the restaurant hopes to increase collaborations with local breweries, wineries, and distilleries like Black Button to draw midweek patrons.

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Interior shots of Lento in Village Gate Square.

It's also part of the reason he's invited Finger Lakes wineries to hold wine tastings in the bar area (the most recent being a fleet of local rosé wines). Rogers believes, firmly, that Finger Lakes wines are world-class.

How can local consumers be more educated? Can farm-to-table still mean something, when it's used so widely? In a word, yes. "You're supporting your community," Rogers says. "These farmers are your neighbors. You're not buying food from other states or countries. You're keeping your money in Rochester, in Monroe and surrounding counties."

He understands money is a consideration for many diners, but emphasizes the value of local. "America is the land of McDonald's and 'How many calories can I get for the lowest amount of money.' That's almost engrained in our DNA at this point," he says. "When you go out to eat, you expect to be able to have lunch for the next day because of huge portions. I don't know how to change people's minds about that."

But he's going to try.

Local food "is going to cost more than mass-produced, factory farm food," he says. "But food is essential, and if your body is a temple, then what you put in it should be of the highest quality."