First of two articles.

In military conflicts, including the current ones, the US has relied on thousands of foreign soldiers and contract workers. Drivers, nurses, cooks, construction workers, translators: all have supported US troops in combat.

When the conflict is over, most US military personnel leave. But for many of the foreign soldiers and workers, once they have aligned with the US, going home may not be an option. And although they worked for the US military --- sometimes even protecting US soldiers --- they are not automatically given citizenship or asylum here.

For Oupekha Keomuongchanh (O-pea-ka Cow-mung-john) and Farid Ferdows (Far-reed Fur-doughs), affiliation with the US Army has taken them on an unusual personal journey. For Keomuomgchanh, it began during the Vietnam War more than 30 years ago. For Ferdows, it is just beginning.

Both men live in Rochester, and their experiences, though years apart, bear striking similarities. Each is from a region of the world wracked by decades of war. Each served US interests in one of those wars, and their work for the US Army put them at risk. Keomuongchanh could not return to his home in Laos after the war. And although Ferdows could go back to Afghanistan, it would be dangerous if he weren't with coalition forces.

A small, thin man now in his late 60's, Keomuongchanh raised his family here, watching his children seize the opportunities he says weren't available to him as a child. And he has been an active member of the community, helping other Laotians settle here.

Ferdows, 23, is living with US Army Commander Tim Mueller and his family in Irondequoit. Mueller befriended Ferdows while serving in Afghanistan on his first tour of duty.When he returned to the US in 2002, the two kept in touch, and they met again when Mueller returned to Afghanistan for his second tour in 2004. This time, he began helping Ferdows get a student visa, a difficult task after 9/11. Now a student at MonroeCommunity College, Ferdows hopes to return to Afghanistan one day.

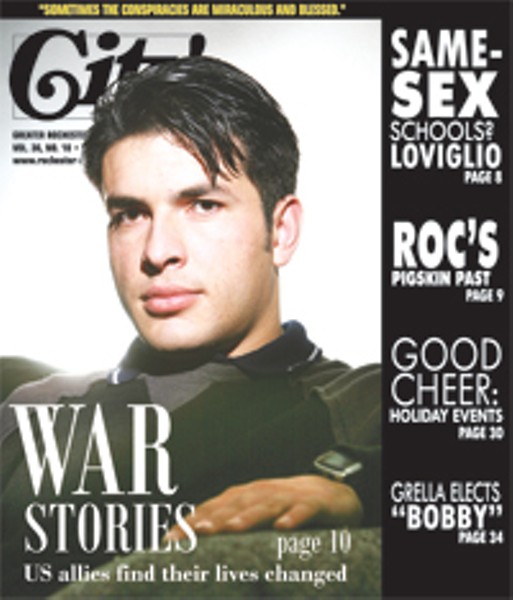

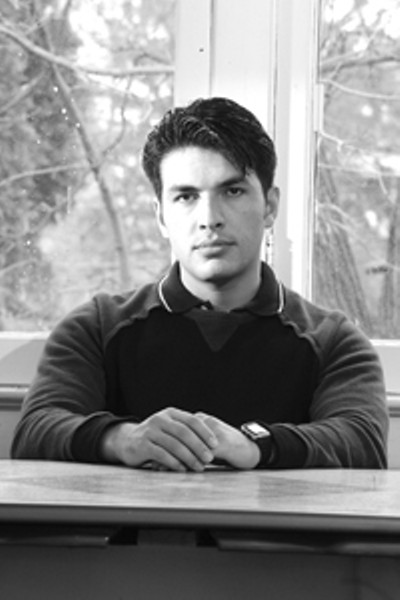

At the Muellers' home in Irondequoit, Ferdows comes to the door. Two dogs, an elderly Pug and a Lab mix, shuffle around his legs. Ferdows is tall, fit, and good-looking. He's also far from home. Born in the Logar province of southeasternAfghanistan to a family of modest means, he grew up in a country ravaged by war.

The country has experienced conflict throughout much of its history. Americans, however, are most familiar with the conflicts of the past 30 years, including the Soviet Union's invasion and nine-year occupation, which ended in 1988 with a humiliating retreat from Afghanistan's guerilla fighters, the Mujahidin. That was followed by a period of civil war that ended with the Taliban militia taking control and then, in October 2001, with US forces overthrowing the Taliban following the 9/11 attacks.

Ferdows' memories of childhood include his father being hit by rocket shrapnel and a mortar round striking his home, critically injuring his grandmother. As the Soviets blasted the Mujahidin in the rural areas of Logar, his family fled north for safety among relatives in Kabul, Afghanistan's capital city. He remembers evacuating and seeing the bombed and still smoldering homes of his neighbors --- and the sight of dead birds on roads and walkways.

"The war with the Soviets was really a resistance to taking our land," says Ferdows. "Between the Soviets and the Taliban, the country was drained. Professionals like engineers, teachers, and doctors fled to Pakistan. The only people who remained were poor, with nowhere to go."

While most of the fighting with the Soviets took place in the mountainous countryside, the war against the Taliban involved some of Afghanistan's larger cities.

"Kabul was still perfectly peaceful place, a beautiful city before all the fighting began with the Taliban," says Ferdows. "Now, when people say it is a soulless city, that's what they mean. All the beauty is gone. Where I lived, there were about 100 families. Now there may be two families left. You have to keep moving from one province to the next to escape the fighting --- or go to Iran or Pakistan."

When classmates and other people learn Ferdows is from Afghanistan, they are curious, but he says he has difficulty explaining what life was like under the Taliban because it was more brutal than anything most Americans have experienced. "I'm convinced that I can never express what it was like," he says. "People talk about North Korea, how the people are literally starving. It's the same thing. They have nothing, no food, no jobs."

"All that people thought about every day was just getting enough to eat," he says. "'How am I going to make it through today? How am I going to feed my children?' That's why most of the young people my age spend their days trying to figure out ways to leave. They want to go to Denmark, Holland, or Norway."

Many people are so desperate, Ferdows says, that they hide in containers and are smuggled out of Afghanistan and into other countries with shipments going to Europe.

"Some succeed, some don't make it," he says. "I am ashamed to admit it, but I always planned on leaving, too."

Ferdows says his parents raised him and his three sisters and two brothers with little money, but even under the Taliban, they found a way to keep him in one of Kabul's more prestigious schools. Instead of history, math, and science, however, most classes focused on religious doctrine.

But he did learn to speak English, receiving advanced certifications in language and computers. He thanks his uncle, a professor at KabulUniversity, for telling him that learning English would be the key to his future.

In December 2001, Ferdows got a job with a British civil-affairs team working under US command.

"It was a new concept --- the Provincial Reconstruction Team --- that was partly intelligence gathering, PsyOps, and construction with the overall purpose of assisting the government in entrenching its authority outside of Kabul," says Ferdows. "We went on patrol with US Special Forces from Kandahar to the Pakistan border."

Ferdows helped with humanitarian needs such as providing food, clothing, and medical care to villagers caught in the crosshairs of the conflict. But his primary job was translating documents from English to Pashto and Dari, part of an effort to rebuild Afghanistan's infrastructure led by the US Agency for International Development.

Within a few months, he was recommended for a job with a US civil-affairs team, where he was elevated from translator to interpreter and liaison officer. That's where he met Army Commander Tim Mueller of the 401st Civil Affairs Battalion, leader of a largely Upstate New York reconstruction crew.

The war had destroyed roads and schools, and some villages had no water. The reconstruction efforts have been massive, complicated, and dangerous, often slowed by sabotage and corruption.

"You're coming into these towns with a $30,000 contract for repairing a school," says Mueller. "But it's like a million dollars there. It really represents a lot of money."

Mueller says this kind of situation is where Ferdows shone.

"There's a significant difference between being a translator and an interpreter, from my position," says Mueller. "You really need someone that not only knows the language, but also understands the people and the culture. It has to be someone who can read the situation and get you through it. You have to have someone you can trust. The Brits told us, Don't go anywhere without him. Farid was the baby of this crew, but he was with us 24/7."

One of Ferdows' most valuable talents, says Mueller, was explaining the Army's motives to the villagers, who were typically suspicious of Westerners. He had his choice of interpreters, he says, but Ferdows was the best because he knew how to work with the Northern Alliance, the tribal coalition united against the Taliban.

"We just couldn't go in there cold," says Mueller. "The warlords were in there with their hands out to them for these contracts. It was very tricky, because there is a ton of corruption. It was difficult to keep them from only hiring their own family."

Despite tense moments when he was pinned down by gunfire, Ferdows says, he was never afraid.

"I knew I was doing something noble," he says. "We've had so many things go wrong for so long. I knew I was doing something good for my country."

The job hazards for interpreters didn't stop with getting caught in a roadside battle. Most interpreters are threatened from within their own communities, says Ferdows. And the main goal is to avoid notoriety.

"The Taliban wouldn't be the ones to come after you," he says. "It would be someone you knew, a neighbor or cousin. Jealousy is powerful. If you have nothing and you think someone you know has so much more than you, but they are unwilling to share, it causes mistrust. You have to learn to be very discrete."

Although he wanted to leave Afghanistan, Ferdows says, his goal was to return home to a free country he could help rebuild. He planned to come to the US to study on a student visa, and that seemed possible until September 11, 2001. Then, he says, the doors closed, especially for young males from the Middle East and Afghanistan.

"I just went forward working with the British team and later with Tim, and didn't think much more about it," he says. "After 9/11, I didn't know if it would ever be possible. It was hard to tell what was going to happen."

But Ferdows and Mueller didn't give up. In 2004, they began planning a way for Ferdows to come to the US to study.

Getting into a US college was a breeze for Ferdows. His applications were readily accepted at both MCC and SUNY Brockport. But a mountain of paperwork and government regulations stood between him and the student visa, testing his persistence and endurance for the next two and half years. The application process involved a letter-writing campaign, with Mueller and Ferdows seeking recommendations from military commanders and US State Department officials. That was the easy part, since all were eager to help Ferdows. But taking the mandatory English test proved to be another twist in Ferdows' long odyssey.

The broken Afghan government was unable to offer the test, so Ferdows had to make the journey, mostly under cover of night, from Afghanistan to Istanbul, Pakistan.

"It is not so much the distance," says Mueller. "It was traveling as inconspicuously as possible across the Khyber Pass, which is one of the most lawless territories you can imagine."

Ferdows went through remote and unfamiliar mountainous terrain, home to drug smugglers, traffickers of human cargo, and terrorist camps --- about the distance from Canada to Mexico. He couldn't reveal the purpose of his journey or his real destination.

"If you say you're going to the US Embassy or you're getting a student visa to study abroad, it is assumed you come from a wealthy family," he says.

He arrived safely in Islamabad and took the test. But dates on some of the papers needed for his visa had expired, which required another trip --- this one to New Delhi, India.

"The rest was in the hands of the US Embassy," says Mueller. "We knew it was going to be difficult. They had no interest in sending young men from here to the US. There just weren't enough assurances for them, so we didn't know until the very last minute if he was going to get it."

Sitting in the Muellers' dining room, Ferdows says he has many of the same interests as any college student. He marvels over little things, like 24-hour access to the internet. He chats with his brother when he can. He would like to transfer from MCC to NazarethCollege, a choice that had been unheard of in Afghanistan. There, students lucky enough to attend college were told by the Taliban what courses to take and where.

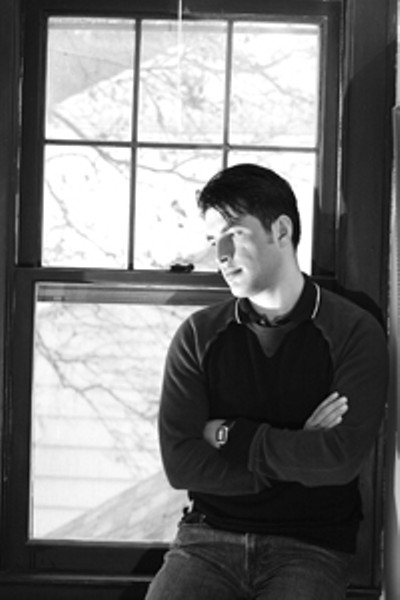

The Muellers have opened their home to him, almost as if he were an adopted son. Mueller and his wife Marti already have two daughters about to graduate from college. Now they plan to help Ferdows do the same thing.

"My wife and daughters have been wonderful," says Mueller. "I know it was asking a lot of them. They had only met him once over Christmas in Germany, so they didn't really know him the way I did. And I just showed up with a guest in tow."

And Mueller had to gradually gain the approval of Ferdows' parents.

"I didn't want them to think I was just taking their son," he says. "I think they knew that I could help him, but they also worried that he might get into trouble. They hear the way some American college kids act, and they didn't want their son to lose his values. I had to assure them that we would take good care of him. And he would still be their son when he sees them again."

Ferdows has made a few friends at MCC, and he's met other Afghans living in Rochester. Although he had read that some Americans were wary of foreigners due to 9/11, he says he has never experienced prejudice when people hear he is from Afghanistan.

"I've been treated very well," he says. "I didn't really know what to expect, especially with 9/11 and all. But mostly, people just want to ask questions. They want to know what it is like over there, and how is it different from here."

Despite everything they have been through, he says, the Afghan people are a proud people.

"We take care of our sick and our elderly," he says. "True, we are very poor and there are beggars, but orphans and homeless people, they are alien concepts over there."

And he worries that Americans may see Afghanistan as having no strategic value, that it is nothing more than a country of poppy growers.

"I don't believe that poppy is a problem," he says. "We don't have addiction, and the statistics are very low for people who actually use drugs. We are talking about a poor farmer that needs a crop for money. If you burn his crop, the ramifications are huge. If he owes money, they will come and take his daughters and turn them into sex workers to pay off his debt."

His worse fear, Ferdows says, is that America will just pull its troops out from his country before the government can get back on its feet.

"I don't understand why so many people are shocked to learn that there are still problems over there," he says. "I am afraid the people there will just be left behind. If that happens, it will turn into lawlessness. This is why the Soviets came into Afghanistan. The government was so weak, it was about to lose power. So they just invited them in."

Next week: Oupekha Keomuongchanh's journey from Laos to Rochester.