There were no slurs, no outright harassment. Nobody even called him a name, as far as he can remember. But the tension, the sense that others saw him as different somehow — less — was a millstone that Lieutenant Lawrence "Shawn" Brumfield says he carried every day for about half of his 15-year career as a Rochester firefighter.

"It wasn't everybody, but it was enough to be a disturbance," he says. "It almost translated into you starting to doubt yourself."

Brumfield was part of the second class of students to graduate from a firefighter trainee program formerly at East High School. The purpose of the program as it existed then was to introduce interested East students to a potential career in the fire service, and to also increase racial and gender diversity in the RFD's ranks — a longtime goal of city officials.

Somewhere along the line, though, the program stumbled. And part of the fallout, Brumfield says, was a divide between the East program graduates who went on to become firefighters and some of the rest of the RFD's rank and file.

Those directly involved with the East program say bumps in the road are to be expected when you're trying something new and innovative. Improvements have been made and will continue to be made, they say, as the program evolves.

- PHOTO BY MIKE HANLON

- Students Teodoro Santiago and Melissa Calkins practice CPR during class.

But others suspect something more underhanded, and systemic. The leadership of the fire union questions whether students in the East High program were held to a different, possibly lower standard than the candidates who joined the department via the traditional route — just so the city could meet diversity goals.

"You've got to be competent in this job," says union president Jim McTiernan. "If something goes wrong, it's not a paper cut. Somebody can die."

And McTiernan and others say they worry that the same problems will plague the latest iteration of the program, which kicked-off this school year. The Career Pathways to Public Safety Initiative, which replaced the East program, provides job information and training in the fields of fire, police and security services, emergency communications, and emergency medical technology to interested juniors and seniors in the Rochester school district. The program is now held at the Rochester Educational Opportunity Center downtown.

"This goes back to, what are we doing to kids?" McTiernan says. "What are you willing to do, to get numbers for some reason, to children? Are we putting kids [in these programs] who really don't know what's going on, to satisfy some adult goals? That's the real question."

The East program did have success stories. Brumfield, only the fourth black male in the history of the RFD to make lieutenant, is one example. Former Rochester Fire Chief John Caufield says that approximately 10 percent of the department is currently made up of graduates of the East program.

But housing the program at East and limiting it to East students narrowed the pool of potential participants. And a program that was supposed to be for the best and brightest seems to have lowered the bar at some point.

"I don't think anybody really was completely satisfied with the level of success we had there," Caufield says. "When you have a decreased number of students applying, and certainly there's always been pressure to have a viable program at East High, we did find ourselves having a real difficult time recruiting quality students. We were forced to consider kids who really didn't meet the mark. Did some get through? Possibly."

But both Mayor Tom Richards and Caufield point out that every recruit, whether you're talking about the old program or the new, still has to successfully complete the intense, 24-week fire academy before becoming a firefighter. Unqualified candidates are sure to be weeded out there, they say.

"[Those] standards have only gotten more rigorous over the years," Caufield says.

According to data provided by Molly Clifford, the city's director of fire administration, 91 students from the East fire program passed the required exam from 1995 until that program ended in June 2012. Of those, 71 went on to the fire academy, and 48 are currently members of the Rochester Fire Department.

Clifford, who wasn't with the RFD for the bulk of the East program, says it appears that baseline standards for that version of the program weren't always strictly followed.

"It wasn't a conspiracy," she says. "People really want to help these kids. They want them to be successful. And I think the problem was people tried to support them and get them through in a way that didn't help in the long term and made it very challenging for them when they got to the academy to be able to keep up."

"We recognize that we're not doing the kids any favors if you prop them up," Clifford adds.

Fire union president McTiernan says the East graduates who went on to become firefighters were treated the same as everyone else. Once they got through the academy, he says, they had proved their mettle.

But Brumfield says that's not the case, because he lived it. He says he believes the color of his skin and distrust of the East program caused some to view him with suspicion or contempt.

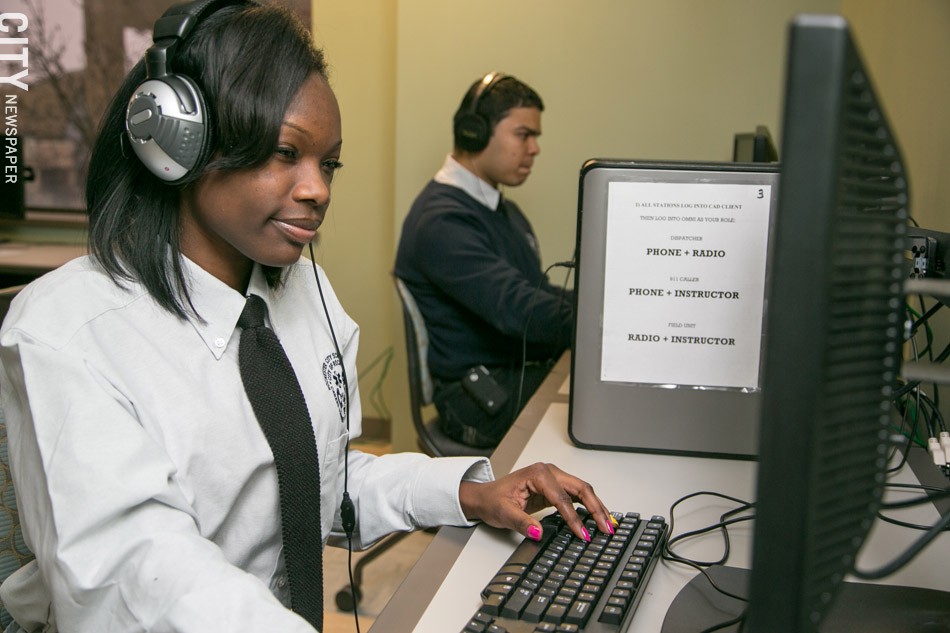

- PHOTO BY MIKE HANLON

- Students Amina Avjam and Abismael Diaz train on the 911 call center simulator.

"They felt we weren't up to par, or we didn't deserve it because of the route we came, 'You didn't get here how I got here, so you don't deserve to be in that spot,'" Brumfield says. "It was something new; people didn't understand it. And the confusion led for some to animosity. Some of it was based on ignorance; people were making assumptions about people they didn't know."

The pushback made him second-guess himself and his choices, Brumfield says.

"I couldn't buy into it," he says. "I would say past half my career, I still wasn't sure this is what I wanted to do."

Clifford says you have to be careful not to paint the whole fire department with the same broad brush, and that the majority of Rochester firefighters were and will be welcoming to graduates of the city school district's fire program.

"As a rule, the firefighters are very open to everybody," she says. "I think there may be a small group of people who cast aspersions on these kids. I absolutely think that if these students are successful in the city school program and in the academy, everyone will have a completely open mind about their ability to be firefighters."

Brumfield says it was only when he realized that other people's negativity had nothing to do with him, that he settled into the job — about seven years into his career.

"I got to the point where I felt good in myself," he says. "When I got there, then all of the outside noise didn't matter. That's when everything started to pan out for me."

The union has practical and philosophical qualms about the fire training program, both when it was at East and the redesigned program at the REOC. McTiernan says the city is snatching up vulnerable youngsters and setting them on a career path that serves the city's self-interest. Students are eligible for the Career Pathways program in their junior year of high school.

"I wouldn't let my child in that program," McTiernan says. "I think it's terrible. I didn't come to this job limiting myself to this is what I was going to do after high school. I finished college. I had a career. I decided this was what I was going to do when I was 28 years old."

Teenagers aren't physically or mentally ready for the rigors of fire training, he says.

Mayor Richards says he resents any implication that the city is exploiting young people for its own ends. "I know Jimmy [McTiernan] is a world-famous psychologist," Richards says sarcastically, "and I appreciate his input on this issue."

One of the reasons the city and the school district broadened the program to include police, emergency communications, and EMT is so young people have options, Richards says. And the rigorous nature of the program might motivate students in other areas of their lives, he says. The students in the REOC program also receive guidance in life skills like money management.

"We've done a good thing here," Richards says. "And with all due respect, many of the people in the union made this choice at 18 years old, when they were in high school."

The union should be supportive, he says, because the students who decide to pursue firefighting after graduating from the program really know what they're getting into: they'll be better prepared, and less likely to wash out at the academy.

The union also has questions about the test the REOC students have to take to become firefighters. Union members were told when the East program began, McTiernan says, that the students would be taking the same exam as everyone else. But that didn't end up being the case.

"They did take a different test, it's true," Richards says. "Whether it [was] easier or not is not clear. I'm not willing to say it was easier." (Caufield says opinions on the test's difficulty are subjective. Tassie Demps, director of the Bureau of Human Resource Management for the City of Rochester, says the test was not easier.)

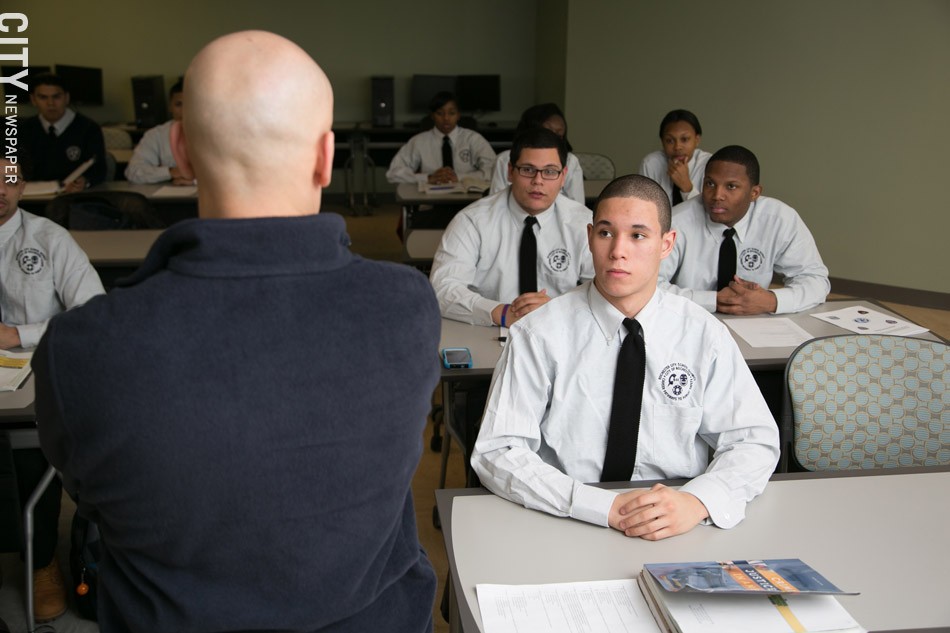

- PHOTO BY MIKE HANLON

- Students listen to instructor Mike Marcano during a law enforcement class, part of the Career Pathways Program.

Officials worried, Richards says, that the students would get tired of waiting for the traditional process to play out and would find other employment, join the military, anything but become a Rochester firefighter. That would negate some of the value of the program, he says.

Richards says he made a commitment to significantly improve racial and gender parity in the fire department, and the testing issue was part of that, as was revamping the overall hiring process for the RFD.

"We've been talking about this for a decade or more," he says. "And for some reason it never got resolved. We just simply decided, this is going to get resolved."

The changes, according to city officials, are producing results. The most diverse recruit class ever is currently training at the fire academy. (In 2010, the RFD had 407 white males, 11 white females, 37 black males, 40 Hispanic males, and one Hispanic female.)

The students in the redesigned program will be given a city-created test. Demps says the city used to create and administer a number of employment exams for various jobs, but it became cost-prohibitive. The city still creates local exams for select public-safety jobs, she says, and the rest take civil service tests.

At the core of the union's concerns seems to be a lack of communication. McTiernan and other members of the union say they were given only one perfunctory meeting with city officials about the new program — and that wasn't until after the Career Pathways program had been up and running for months.

"It was embarrassing for them," McTiernan says. "Nobody can answer our questions. All we hear is [the students] won't be taking the same test. And that is unacceptable. Nobody on this job cares whether you're white, black, green, purple, or pink, as long as you can do the job. That's all there is to it."

Forty-two students — juniors and seniors — are enrolled in the Career Pathways to Public Safety program this school year. To participate, they need a 2.0 grade-point average in their core subjects, 93 percent attendance, parental consent, school counselor sign off, and two letters of recommendation. They must also participate in an interview.

Juniors take a career awareness course, spending nine weeks on each discipline in the program: police, fire, emergency communications, and emergency medical technology. The purpose is to expose them to each field so they can pick one in which to job train in their senior year.

The students wear uniforms, and the school has a paramilitary feel — the students stand at attention when someone enters the classroom. Late students are made to write 250-word essays or do 100 pushups; most choose the pushups.

The program's coordinator, Robert Poles, is a retired recruiter for the Rochester Police Department, and instructors include public-safety professionals with decades in their chosen fields. In addition to classroom work, students do job shadowing, ride-alongs, field trips, and other activities. Students are also provided with mentors from their chosen career paths.

"We're breaking new ground by providing new opportunities for our young people," Poles says. "If we can just get a couple of kids through and people see it, this thing is going to catch fire. We're going to need more classrooms. I really believe that."

Poles says the program is already paying off. The Monroe County Sheriff's Office contacted him about candidates for internships, he says, praising the REOC students' maturity and the quality of their resumes.

- PHOTO BY MIKE HANLON

- Lawrence Brumfield: fitting in at the RFD wasn't easy.

Some students who successfully complete the program will be immediately eligible for jobs. Graduates of the police program will be certified security guards. And Rural/Metro, the city's ambulance-service provider, says it will hire all students from the emergency medical program who successfully pass the EMT certification training. "It will be a direct hire," says Beverly Gushue, director of career and technical education for the city school district. "They will have a job."

Now that Brumfield has settled into his role as a Rochester firefighter, he says he feels an obligation to help those who come after him. Firefighting has historically been the territory of white males, and it also tends to run in families. Many people in the fire service have fathers, grandfathers, and brothers who are firefighters, too.

Former Chief Caufield says that legacy perception is probably always going to be a barrier to recruiting people of color to the fire department.

"You tell a young black boy that he can be a firefighter, but you don't have any black firefighters. Or they don't see them," Brumfield says. "They always see black drug dealers."

The school district fire program is a good thing, he says, because it provides never-before-contemplated opportunities for some young people.

"You had a lot of people [in the East program] who turned their lives around because they had something to reach out for," he says.

Brumfield wanted to be doctor before his father pressured him into the fire training program at East High. His father worked at East, Brumfield says, and was impressed by the program. Brumfield says he hasn't given up on medicine entirely; he's in graduate school now to become a nurse practitioner. But he says he doesn't have immediate plans to leave the fire service.

"Because there are not too many people of color in the ranks, I think it's important for everyone who gets there to trail blaze as far as they can," Brumfield says. "I don't want to be fire chief, but I think that I owe it to myself and to those behind me to [go] as far as I can. I believe I was placed in the situation I'm in because I have something to give."