The oldest of Francine Lynch's three children will graduate high school next year and plans to go to college. Lynch works for the University of Rochester, so her daughter could go there for a fraction of the normal cost, but her daughter is interested in a career program that the UR doesn't offer.

Finding the money for her daughter's choice school is giving Lynch night terrors.

"It makes me very anxious and sleep-deprived," she says. "I wonder if I'm going to be in debt for the rest of my life."

Lynch says that she always imagined that she would pay for her children's college education. Four years at a state college seemed doable once, she says, but now that appears out of reach, too.

"I've told my daughter that her job is to apply for scholarships, scholarships, scholarships, because I am just overwhelmed with how much this is going to cost," Lynch says.

Lynch is not alone; many college students and parents share her anxieties. This helps explain why free college, a key part of Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders' campaign platform, is so appealing.

For some, free college is a battle cry for social reform that crosses generations. The concept is especially appealing to younger people impacted by record high amounts of student loan debt who, as a result, are delaying other important life decisions such as buying a home, marrying, and starting a family.

Sanders and Hillary Clinton, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, both promote "forgiveness" programs for student loan debt.

For others, free college is little more than a shrewd political ploy wrapped in an appealing populist message.

But either way, making college free does not make its costs disappear. And a national discussion about exactly how higher education is funded in the US, its true costs, and what can be done to make it more affordable is long overdue, many say.

Even experts familiar with the dizzying logistics of education finance admit that it is an incredibly complex and intimidating world to navigate.

Talk about free college in the US has been around for some time, says Heidi Macpherson, president of the SUNY College at Brockport. Most of the proposals concern free two-year public or community colleges and involve what are referred to as "last dollar policies." When students receive their financial aid, grants, and scholarships and it's still not enough, free college advocates have tried to find ways to fill that gap, she says.

- PROVIDED PHOTO

- Heidi Macpherson

But it's a vexing challenge because each person's situation is different and one-size approaches won't meet everyone's needs. What is often overlooked in those conversations is that tuition is only a part of the cost that needs to be covered; some colleges charge administrative fees, and there's the cost of textbooks, food, and housing.

"One of the inherent problems with this kind of narrative is that it never appreciates the nuance of things," Macpherson says. "This kind of broad brush stroke is never close to the reality."

Macpherson says that a big reality often overlooked is that while higher education is not free in the US, the federal and state governments do contribute significantly to its costs.

"I think that students and parents don't understand that they've never paid the full cost of higher education," Macpherson says. "Their tuition doesn't actually cover the cost of educating students, and I think Bernie Sanders has given us the opportunity for that public debate."

Sanders makes the case for the US to join some European countries by looking at college more as an extension of public K-12 schools. Access to K-12 in the US is universal and free, and many states have added universal free prekindergarten to that package. Now it's time to make college free and universal, too, the argument goes.

Sanders says that one way to do that is to redirect federal funds — tax revenues — to cover about two-thirds of the cost of public colleges. He wants the money to come from a tax on Wall Street transactions. The states would have to come up with the remaining third.

Millions of Americans seem to wholeheartedly agree with Sanders, at least in principle. But economic professors from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, Robert Archibald and David Feldman, have looked at the issue of free college extensively and they've come to a different conclusion.

The authors of "Why Does College Cost So Much?" say that Americans, ironically, are poorly educated when it comes to how higher education in the US is financed. And the professors don't see how Sanders' approach would work because there are serious structural obstacles that would need to be addressed by Congress and state legislatures.

In an article they co-wrote earlier this year for the Washington Post, Archibald and Feldman talked about annual tuition rates under the Sanders model.

- PROVIDED PHOTO

- David Feldman

"In 2013-14, the average level of in-state tuition at the nation's four-year public universities was $8,312," they said. But some states have a higher average tuition because the amount they appropriate to higher education is lower. Families in the high-tuition states stand to receive a larger benefit under the Sanders plan while families in other states would see a much smaller benefit.

It's hard to imagine members of Congress in the "losing" states going along with this plan.

What's needed instead is a clearer understanding of college financing, Archibald says. The College Board publishes annual reports about trends in higher education financing and the findings might surprise some people, he says.

For instance, the 2015 report shows that the average annual rate of tuition increase at private, nonprofit four-year schools has declined since 1985-86 from about 3.5 percent to 2.4 percent for 2015-16.

But tuition at many public or state colleges and universities is increasing at a higher rate, so students and parents are paying more of the cost. And if you're an out-of-state student planning to attend a public school, you can expect to pay more, too.

Adding to the confusion about the cost of college is how the institutions market themselves. There's often a striking difference between the price that colleges and universities advertise and what many students actually pay. Many students don't pay the full sticker price once grants, scholarships, and sweeteners that institutions offer to attract high achievers are factored in.

William and Mary's David Feldman says that the US basically has two programs to help students pay for college.

"The federal government and the state government intervene in the higher education market in complementary but very different ways," he says. "The federal government provides aid through Pell Grants to students through a need-based qualifying formula."

The Federal Pell Grant Program has several advantages, Feldman says: it's portable and follows the student; it can be used at a public school or a private nonprofit school; and it's targeted to high-achieving students from low-income households. And since it's a grant, the money doesn't need to be repaid.

The federal government has increased the amount of money it distributes through the Pell Grant Program, but critics say that it's not nearly enough. And many poorer families don't know how to complete the application and often fail to provide all of the information needed, Feldman says.

State funding for higher education works differently. States such as New York and California, for example, have built quality systems of higher education, and tuitions have been historically low for in-state students. Brockport costs $6,470 a year, for example. And if a student starts out at Monroe Community College and transfers to Brockport after two years, for instance, he or she is able to earn a college degree fairly economically.

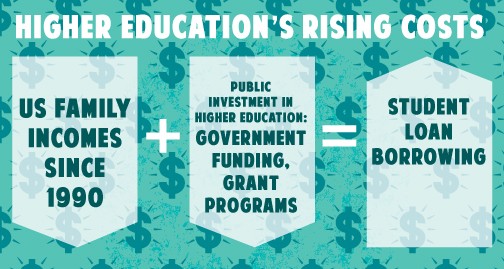

The lower-cost state systems are generally seen as long term public investments that benefit state economies. Unfortunately, though, while the federal government has increased its contribution in the form of Pell Grants, some states have passed more of their costs on to students.

Still, this two-pronged approach can significantly reduce what students and their families actually pay for a college education compared to its real dollar costs, Feldman says.

He says that the public's anxiety about the cost of college is at least partly due to some other factors, starting with income distribution in the US over the last 40 years.

"If you go back to the 1970's, you are in the halcyon of income equality," Feldman says. "Income from the late 1930's to the 1940's and the World War II era right through 1970 was at its most equal in recorded history. In the early '80's that started to change."

What's different today is that income growth is occurring at the top, he says. The top 1 percent has received nearly all of the gains from the economy over the last 40 years, he says. The bottom has received almost nothing. And while those individuals who you might call upper-middle income and above are doing better economically than the average person, they've watched their income flat line, particularly over the last 15 years.

It's the students from households in this latter group who are generally feeling more of the financial pinch because they are less likely to qualify for federal aid. Those students and students from wealthy households are more likely to pay the full costs of college, according to Feldman. And they still have all of the other economic pressures, including the rising costs of everything from food to heat and electricity.

Feldman says that it would help if more students and families received better financial counseling well before the college years arrive. Many of the horror stories about high student debt are the result of poor decisions and a lack of financial planning, he says.

And there are studies that support his point. They show that many students don't know basic information about their loans, including the amounts they've borrowed and at what interest rates.

Some critics of the free college concept see this as a prime reason why some student debt is not necessarily a bad thing. Without something at stake, it's too easy to let the meter run on someone else's dime, they say.

Could more be done to reduce the cost of higher education? Feldman says that more restraint could be shown in deciding what improvements should be made to a college or university. For instance, is a state-of-the-art gymnasium and pool a necessity?

Of course not, Feldman says. But students and their families ask for all of the best amenities, he says, and if they don't get them, they'll select another school.

Many experts say that a discussion about the cost of higher education needs to take place in broader terms instead of through the lens of campaign slogans.

For instance, if Americans decide that free college is more or less a constitutional right, should families who can afford to pay be asked to contribute, anyway? Should taxpayers subsidize children from well-off families at the same rate they do children from poorer families?

"So the question in my view in an era of limited resources is do we want to put all of our resources into everyone equally, or do we want to marshal our resources for those who need it most?" says SUNY Brockport's Macpherson. "That's a philosophical debate that's hard to have."

Secondly, universal free college would mean that considerably more of every tax dollar would have to be committed to higher education, and Macpherson isn't convinced that the public is ready to pay what Europeans often pay in taxes.

It's likely that cuts would need to be made to other government programs, she says, or taxes would need to go up substantially for the greater good of the country.

"I don't know of very many people who are saying 'I want to be taxed at a higher rate,'" she says.

And some people are confused about free college as it relates to European countries, she says. Macpherson began her teaching career in England when college was free, but students there now contribute to their college education, she says. And the amount students pay has risen steadily.

Another issue that is starting to receive more attention is whether a four-year college education is even appropriate for everyone. Many high school teachers lament that a significant portion of their students is neither capable of doing college-level work nor interested in going to college.

Many students want to pursue trades and aren't adequately guided in that direction, often because the programs have been cut, teachers say.

William and Mary's Robert Archibald agrees.

"I think where we let students and families down is in the assumption that college is the next step for everybody," he says. "We do a very poor job as a country of vocational training for the kind of high-skilled jobs we have. They're the kind of technical manufacturing jobs that are still in this country."

There's also a danger that free college would lead to lower standards so that college graduation rates show favorable outcomes, Archibald says. There's a reason why only a small number of applicants are accepted to schools such as Harvard and Columbia, he says.

(Francine Lynch is news editor Christine Carrie Fien's sister.)