Law enforcement agencies around the country have touted their community policing efforts for at least 30 years.

But does it work? Are cities any safer when police walk their beats, go to neighborhood meetings, empanel advisory boards, and help residents solve everyday problems – from barking dogs to abandoned homes or drivers speeding down residential streets?

None of those things does much to lower crime rates, says John Klofas, a criminal justice professor and the founder and director of the Center for Public Safety Initiatives at Rochester Institute of Technology. One reason is that a very high percentage of the most serious crimes is committed by a small number of persistent felons – who are very unlikely to be engaging officers outside the context of a 911 response.

But, Klofas says, when it's done right – and with a commitment from residents, political leaders, and the police force—community policing can improve often-strained relations between the police and citizens. Community policing, he says, can build trust between the police and citizens, and that's worth doing, he says.

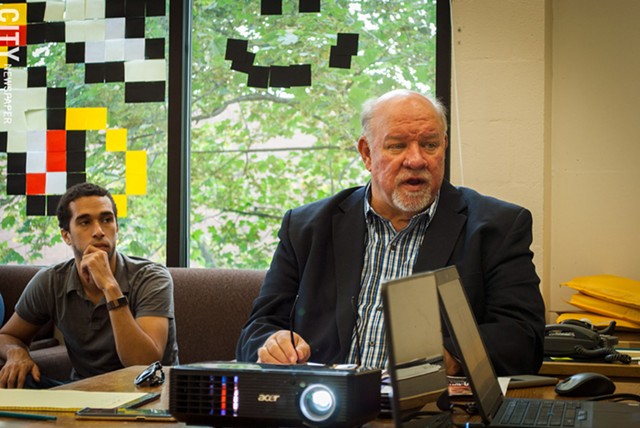

- PHOTO BY RYAN WILLIAMSON

- John Klofas (right), director of the Center for Public Safety Initiatives at RIT, with (from left) Irshad Altheimer, the center's deputy director, and research assistants Chaquan Smith and Aaron Baxter, at the center's weekly research meeting.

The Center for Public Safety Initiatives, under Klofas's direction, performs local research on criminal justice, police, and public safety issues and works closely with its partner agencies, including the city and the Rochester Police Department.

When citizens and officers work together to solve problems in their neighborhood, he says, residents have a sense of empowerment and confidence that they can shape the future of their community.

Like most cities, Rochester has a range of programs that it fits under the umbrella of community policing. Following a controversial 2016 arrest on Hollenbeck Street that led to allegations of excessive police force, Mayor Lovely Warren called for 90 Days of Community Engagement – a series of community forums to assess citizen concerns about the Rochester Police Department. In the spring of 2017, the city released a report on the 90-Days process and listed a number of activities the RPD uses to engage citizens and build strong relationships. Among them:

• Project TIPS: Officers and citizens go door to door in neighborhoods to share information and collect residents' thoughts on neighborhood issues.

• Shakespeare from the Street: In conjunction with the Hillside Family of Agencies, at-risk children and officers develop a Shakespearean production as part of the RPD's efforts to build relationships with neighborhood youth.

• The Police Activities League: Youth and police engage in athletics, arts, recreational, and educational programming.

• Clergy on Patrol: Clergy and officers walk neighborhoods to interact with residents.

• PCIC (Police Citizen Interactive Committees): Section captains and officers meet monthly with neighborhood groups to review crime reports and patterns, quality of life issues, and problem locations.

These activities are fine as far as they go, Klofas says. But, he says, the RPD, like most departments, is structured to respond to 911 calls for service, not to make citizen engagement the top priority. In 2016, the RPD responded to 370,538 calls, down from 444,568 in 2012, but still a huge volume.

During 2016 and 2017, CPSI led a research project – Community Views on Criminal Justice – that used surveys and focus groups to assess citizen perception of police behavior. The groups represented a broad cross-section of the community, including youth, faith-based groups, neighborhood groups, police-citizen groups, reform advocates, homeless people, immigrants, and elected officials.

Not surprisingly, Klofas says, those who work closely with the police on a regular basis – outside the setting of a 911 response – had the most positive views of law enforcement. Those who had little personal contact often felt that their voices are not heard.

Referencing the 90 Days of Community Engagement community forums, one paper from the CPSI project recalls that one resident said he would like the "'us versus them' attitude removed and for officers to answer from the heart when asked a question, not to answer 'politically.'"

The challenge is to build stronger relations in those parts of the community where the police are seen only in their role as enforcers.

In response to police-community unrest and distrust nationwide, President Barack Obama established a Commission on 21st Century Policing, which issued a final report in May of 2015. Among its key recommendations was that departments give more time and attention to training and educating officers, at the academy and throughout their careers, in effectively engaging the community.

That's critical, Klofas says, if the police agencies and the communities they serve are to reap the benefits of community policing programs.

In a recent interview, Klofas discussed community policing efforts and Rochester's challenges. What follows is an edited transcript of that conversation.

- PHOTO BY RYAN WILLIAMSON

- John Klofas (right), director of the Center for Public Safety Initiatives at RIT, and research assistant and graduate student Aaron Baxter.

City: How do you define community policing?

Klofas: The definition has changed over time. In the 80's, it was seen as a significant change in approach to law enforcement: employing strategies to engage the community in problem solving, sweeping changes in police-community relations. Now it's seen as more a set of principles that no one could possibly disagree with. You'll see it reflected in the president's commission – setting up advisory boards, walking beats where possible, procedural justice, which means treating each other with mutual respect.

In its original conception, it was presented as having a strong impact on crime. In general, the research has not shown a strong impact on crime, but has shown an impact on the strength of relations between police and community.

You would think improving relations would reduce crime.

You can make an argument that way. But the offending population, the population responsible for the most serious crimes, is a small percentage of the community as a whole and is a harder one to influence that way.

In neighborhoods where there are people who are pretty engaged, people will sometimes get the cell numbers of officers in the area, and bypass 911. And they come pretty quickly. In Maplewood, where I live, this made people feel connected to the police, but when you have a rash of burglaries, there's not much they can do.

We did about a year of focus groups on police-community relations [the Community Views on Criminal Justice project], and one conclusion was that there are people who love the police, there are people who hate the police, but the vast majority of people are somewhere in between, and their opinions are driven by the most recent experience they've had with the cops. So there are people who can swing in either direction.

How do you describe the state of community policing in Rochester?

They changed back to five sections. And the hubbub was that this is for better community relations. But they never trained anybody. The police departments that are serious about this have introduced the idea in the academy and trained people on it, have supervised people and done things to try to change the nature of the organization. But that hasn't happened here.

So you have people doing pretty much what they have always done in Rochester. And what they have always done has been very much driven by calls for service. Rochester has always been a calls-for-service police department, and cops spend most of their time running from call to call particularly in the evening.

One of the metrics they focus on is length of time in calls for service. And that is a work strategy that conflicts with the time it takes to do longer, more engaged work in the community.

A speedy response seems to be what police expect of themselves and what most people expect of the police: if there's a call, they're going to come right away. How do you break free of that with the existing resources you have?

Other places deliberatively give people time off the call list. The expectation is that there is a certain amount of time during the day when they would not be answering 911 calls unless there is a real emergency. Other places have specialized kinds of units that do community policing and are not typically responsible for responding to 911.

We have some version of those, because we have community police officers stationed at the mini-city halls. These designated community police officers are expected to engage the community differently. But there are not many of them. The bulk of everything the department does is driven by calls for service.

But there are reasons why 911 governs everything, because [response time] becomes the accountability measure for individual officers and the department as a whole. It's the structure of how departments measure themselves. And mayors' offices field all these calls about how the cops didn't show up, and in many cases, they drive people toward that 911 kind of focus.

What are some examples of community policing activities we might want to consider?

The CAPS program in Chicago [Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy] has been very favorably evaluated. It was widespread. They spent a lot more time in the community. People were assigned to community space.

Portland was using 911 to get police to go to neighborhoods to engage in community police work. They structured time for it where the computer would call an officer to report to a particular place – not for hours or days, but for minutes and half-hours. A lot of research on high crime districts [says] that relatively modest but repeated presence by the police is very effective. And at the end, the officer has to clear the call like you would with a 911 call, and so there's a record and they could assess time spent in the neighborhoods. The result was not so much an effect on crime, but an effect on police-community relations.

So in a city like Rochester, how do you move away from a calls-for-service mindset to improving relations between cops and citizens?

There's a Priority 1 call, which is serious, a "get there now" kind of call. Then there are less urgent kinds of calls – if you're calling to report your bike was stolen, for example. In some places, you do not respond quickly to non-priority calls and you use that time for other things.

Some departments make an effort to turn as much as they can over to non-sworn personnel – to do things that cops don't have to do. But the city budget says that the authorized force in Rochester is 728 sworn and 123 non-sworn. Is that normal?

There's no normal. When you look across departments, they tend to vary a lot in terms of number of cops for the population and the number of cops per crime.

We have a lot of cops. Oakland, for example, has the same number of cops and twice our population. When you start going west, the number of cops changes. And cops do different things in different places.

In Oakland, is there much less crime?

They have bigger crime problems than we have. I think it's budgetary constraints that have led to this kind of model. They had in mind a smaller right number to get the job done. As you move west, policing is totally different. They shoot a lot more people, too.

One thing you have to say is that we don't shoot very many people here. When you go into western city departments, it becomes more frequent.

There are a lot bigger distances in some places, like San Bernardino, so there's not the backup. Here, whenever there's a call of any significance, there's backup right there. When there are fewer cops in bigger spaces, you get much less backup.

So community policing doesn't directly reduce crime rates, but if effective community policing helps to build trust, does it help to solve crimes?

I think there does remain a strong belief that improved relationships between police and community will contribute to crime reduction. Of course, you can imagine how complicated that relationship is: complex communities, different crime problems.

Perhaps the most successful efforts have come under the topic of "problem oriented policing," which is generally seen as falling under the community policing umbrella. Problem oriented policing at its best involves police and community identifying problems together and working out solutions – interventions – together.

Is there any evidence that officers who spend some significant portion of their time helping people solve problems and getting to know the community are less likely to engage in the kinds of confrontations that wind up in the headlines?

This is the big question. As a specific and narrow research question there is evidence, but it is not strong and significant research on the subject has started only recently.

There is some data and some theory that argues in favor. It is generally now part of the discussion of what has become known as "procedural justice" – which refers to mutual respect during interaction between police and citizens.

Are there things we could try here to build better relationships?

I think the relationship between cops and the community here is kind of frozen in time in many ways. There's not much that goes on that is specifically designed to change those relationships because 911 is so prevalent.

There are these niches. School Resource Officers are a niche. The community police officers are kind of a niche. They don't represent the usual interactions between citizens and cops.

Should we be paying more attention to community policing?

Certainly President Obama's commission argued that there should be concrete strategies adopted to strengthen the relationships – community advisory boards, or some form of citizen review of police behavior, although they said there was not enough research to support any particular model at this point in time. They said community policing and community engagement are important.

It's a community issue. It's a democracy issue. Police engage with the community, and the ability of the community to in some ways affect the nature of policing and the interactions between citizen and police leads to a more open approach.

- PHOTO BY RYAN WILLIAMSON

- Among the programs the city has created to strengthen ties between the police and the public: the department's mounted patrol.

So it takes a real commitment at the highest levels, not just with the police chief, but with the mayor and City Council?

I think that's right. You need strong leadership to advocate for this stuff all the way up the chain. The chief alone can't do it. There has to be an established community interest. There's a philosophy that has to be adopted by the city as a whole, by its political structure. That's the big argument the president's commission makes.

Does having police visible and walking around in the community have an effect?

Yes, the presence has an effect, and the nature of the interaction has an effect. There's some research on that, although there's also some research that shows cops can be intimidating no matter how much they smile. Everybody knows when the lights go on behind you, it's an anxious moment.

So there is research that supports [doing] this stuff, but also research that says there are limits. Ultimately police are an authority in the situation.

Is there resistance among police offers to this kind of community engagement?

That's hard to say. 911 sets the tone for interaction. If you can escape 911, then you have something different. In our [focus] groups, a bunch of people knew who to call, and had the officer's cell number and knew him personally. They could have a conversation. Other people had no idea who to call, and everything would be done through 911, and everything would be a tenser relationship than the one between people who knew each other.

What we found in those discussions is that there were very different attitudes for people who knew the cop, had his cell number, interacted periodically with the cop, and people who had none of those. That's both a cause and consequence of these relationships.

So I'm not sure it's clear that cops don't want to engage in this. I think they do. And I think there's a fair amount of research that shows the inability to do that becomes a stressor at work. If all you're doing is running around and dealing with people in difficult circumstances, that's a wearing job.

Is there federal money available for community policing programs we might want to consider going after?

There are several places in the federal government that provide training. One is the National Technical Assistance Center, where a city can say: Here's a set of issues we've been having, and then NTAC can find some people to work with you on those issues over a long period of time. A lot of the federal stuff has focused on violent crime, but in the last five years or so, increasingly they've focused on police-community relations.

So the central question is, to the extent there's a lack of trust, how do you build it?

That's exactly right. And to some extent, it's trust for what? And it turns out, it's not trust for major reductions in crime. That doesn't seem to be there. It's trust for better relationships between the police and citizens. It's trust for feelings of safety. It's trust for respect that's going both ways.

Is that even worth doing? You do all these things but it doesn't really affect crime. Is building relationships a law enforcement thing?

I tend to think, as the president's commission does, it has great value in and of itself. The police department, in any community, tends to be the biggest expenditure of tax dollars. And the most frequent contact people have with government is contact with the police. So this is, in many ways, fundamental to the democratic process.

Whether people feel they are subject to an occupying force, or whether they feel their safety is something that emerges from a community effort that includes the police is a very different kind of thing.

I like the way you weave in the question of democracy.

I think that's the core of it.

It's one thing to say you want to have community policing to reduce crime, which may not happen, and another to say we need improved relations to give people a sense that they are empowered, that there are things they can do about their situation, that there are people they can talk to, that the police are there to protect them.

Yes. They can identify problems and be taken seriously.

What you're saying speaks to the trend over several years of dumping surplus military equipment on police departments. When you see these armored vehicles and police in camo, it sure feels like the cops see citizens as the enemy. And now the Trump administration says it will reverse President Obama's ban on the transfer of military equipment to civilian law enforcement agencies.

Ferguson put that stuff on the front page for everybody. And it's not just all of the equipment, it's all of the guys coming back from the military into the police. Because historically, the training for police has been totally different from the training for the military.

But now one of the consequences of all the wars we've been in is that a lot of people are coming back and joining police departments and bringing that training with them. And guys in the military, they point their gun at someone, right? That's the expected, accepted way of handling it. In a civilian police force, you're interacting with people, not doing that stuff.

So you've got this combination of things that have arguably made contributions to the nature of these relationships. And the fight against that is to democratize the police-citizen relationships and give people a sense of power over the situation in their neighborhood.