Whether in literature or cinema, the mystery story provides an endlessly fascinating source for all kinds of narratives. In a sense, all stories, even all sentences, are mysteries of a sort, since we do not "solve" them until they end. The mystery in the new movie "Gone Girl" demonstrates some of the rich potential of the form.

Based on an extremely popular novel by Gillian Flynn, who also wrote the screenplay, the movie initially follows a familiar pattern, then expands in scope and ramifies in different directions, in effect telling a number of different stories. It begins with Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) starting his day, his fifth wedding anniversary, in a bar, appropriately called The Bar, which he owns with his twin sister Margo (Carrie Coon), drinking bourbon and complaining about his wife Amy (Rosamund Pike). He gets a phone call -- the movie never makes it quite clear who calls -- and rushes home to find signs of a break-in and his wife gone.

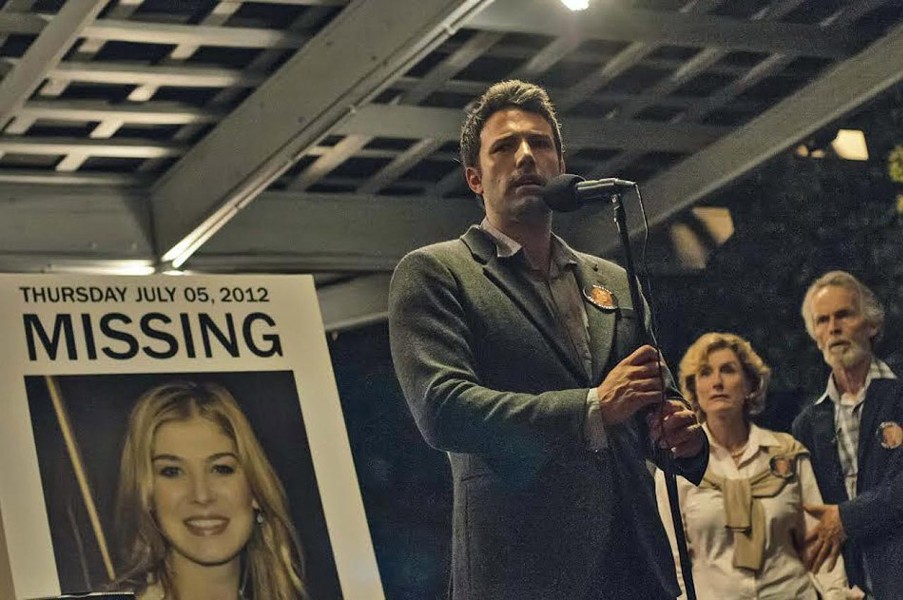

From that moment, the major plot begins, naturally involving the search for the missing woman. The police investigation, headed by a tough detective named Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens), discovers partially cleaned-up bloodstains, evidence of a possible faked intrusion, and inevitably casts suspicion on Nick. She and her partner interrogate him about his marriage, note that he apparently knows surprisingly little about his wife, and start to investigate him and his sister.

Because Amy is the daughter of a couple who wrote a series of famous books based on her personality -- she claims they stole her childhood -- her disappearance intrigues the media, who swarm the Missouri town where the Dunnes live. Amy's parents feed the frenzy, holding press conferences, enlisting the whole town on search parties, making direct appeals to the TV cameras, even setting up a special website and hotline.

As the investigation progresses, a line at the bottom of the screen keeps track of the days of Amy's disappearance; the chronology, however, shifts back and forth through the years of Nick's and Amy's relationship and the present, complicating the narrative with flashbacks and numerous entries in Amy's diary. The diary chronicles their meeting, the romance of their early years, their reluctant move to Missouri to care for Nick's dying mother, Amy's desire for a child, and the gradual deterioration of their marriage. Amy even records her efforts to buy a gun, presumably to defend herself against her husband.

When the police find the diary and evidence of Nick's infidelity their suspicions intensify and the media happily turn him into a national pariah. A particularly vicious cable TV personality -- obviously based on the horrible Nancy Grace -- sets out to crucify him, even throwing in an accusation of incest ("twincest"), apparently just for the sheer sadistic joy of it. Despite the fascination of the mystery itself, in fact, a more compelling subject of "Gone Girl" is the role of the media, the swarms of TV crews that surround Nick's house, the hordes of slavering journalists who dog his footsteps, follow his car, and fling accusatory questions at the press conferences, inciting a national virtual lynch mob.

Under the guidance of a brilliant defense lawyer, Tanner Bolt (Tyler Perry), Nick turns the tables on his accusers, appearing voluntarily on a television show to confess his sins, but also affirming his innocence. The script acknowledges the redemptive power of television -- doubters should recall the cases of Oliver North, G. Gordon Liddy, Mike Barnicle, Doris Kearns Goodwin, and most recently, Bernard Kerik, all of whom regularly appear as talking heads and purveyors of opinion, wisdom, and propaganda. The film even reaches its wonderfully appropriate conclusion by means of a sickeningly hypocritical TV interview.

The mystery plot, equally ironically, depends upon so elaborate and preposterous a scheme, borrowed from "Presumed Innocent," that perhaps the movie needs that subtext. Its cynical view of humanity, of the gullibility of the American people, of the lynch mob mentality of the press emphasizes a surprisingly misanthropic vision, certainly justified by its depiction of some all too familiar scenes of the coverage of notorious criminal cases of abduction, sexual assault, and murder, all of which entertain the public in "Gone Girl" and in reality, every day.