When the Greater Rochester International Airport was renovated in the 1980's, there was a push to have major works by local artists installed there. The new design, in fact, was created with art in mind, and spaces were reserved for site-specific work. This was following a national trend; airports were becoming the sites of important collections of art. The artwork helps form a traveler's first impressions of a region, and it offers a welcome distraction from the hassle of traveling and pre-departure downtime.

County politics, though, messed with the plans to install the art in the regional gateway, and a bitter battle picked up between a group of art enthusiasts and local politicians. Ultimately, the art was installed — only for it to be removed piece by piece over the next 25 years.

An installation of 10 six-foot-tall photographs by artist Richard Margolis is the most recent work to be taken down, and some of the original group of supporters have again rallied to protest the removal. A petition, created by Margolis, now has more than 700 signatures and dozens of comments of support.

- Photograph courtesy of Richard Margolis

- Installation view of Richard Margolis' photographs at the Greater Rochester International Airport. The images have been removed and advertisements have been installed in their place.

It's argued that the Rochester building is behind other airports in having an engaging environment for travelers. The sleek, spacious port feels cold and bland, and while the walls are spangled with advertisements, only a few remaining pieces of the commissioned artwork are sprinkled throughout.

Margolis's striking black and white images not only represented Rochester's identity as the world capital of photography and imaging, they also presented travelers with an idea of what they would find beyond the gates: parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted; the Erie Canal and Genesee River; and the monument to abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

The fight over airport art is one of three major battles related to local arts and history Margolis has been involved in. When George Eastman Museum (then known as the George Eastman House) trustees moved to transfer the museum's collection to the Smithsonian Institution in 1984, Margolis was part of the massive push that successfully kept it in town. He was also one of the most entrenched members of the decade-long effort to save the historic Hojack Swing Bridge — the campaign failed, and the bridge was removed in 2012.

Margolis's current petition calls for three main actions: for Monroe County to restore the removed airport public arts projects; for the formation of a city-county public art commission that would plan and coordinate art in public spaces across the county; and for one percent of all future construction funds to be dedicated to the commission and installation of public art in Rochester and Monroe County.

It's important for the airport to have local art, Margolis says. It provides a sense of who Rochesterians are, and what sets the city apart from everywhere else.

"The airport feels like a mall," he says. "There's practically nothing that isn't franchised there ... nothing that you can't find anywhere else."

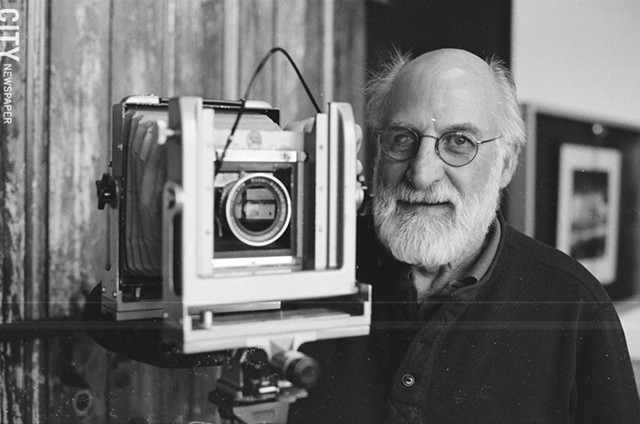

- PHOTO BY MARY ANNA TOWLER

- Advertising has bumped Richard Margolis' installation of photographs at the airport.

Margolis's 10 images were installed in 1994 in two groups facing one another from walls on either side of the airport's long lower level. The photographs would slowly come into view as you took the languid trip down the escalators. Or possibly, they would get those rushing down the stairs to pause on the way to the baggage claim area, which is located in the center of that space. The tall, window-shaped scenes greeted newcomers and welcomed locals home.

Half of the photographs had already been displaced from their original spot about five years ago by the addition of a veterans display area on the west side of the lower level. Those five images were moved upstairs, to a wall directly above the other five. Though the move disrupted his original intent for the work, Margolis says he was content with it.

- FILE PHOTO

- Richard Margolis.

When that new spot was claimed for ad space, the five photographs were moved once more, this time to the sides of support columns just outside of a lounge area.

"They didn't inform me of that ahead of time," Margolis says. He found out while picking his wife up at the airport about a year ago.

When the other five, still on the original lower level wall, were bumped last December by large advertising banners, Margolis was notified via a letter. The letter, from Deputy County Attorney Don Crumb, stated that the images needed to be removed to "pursue an avenue of advertising revenue." A gigantic banner ad for the University of Rochester is hanging there now.

Margolis toured the airport with GRIA Assistant Director Jennifer Hanrahan, to explore proposed spaces for the prints' placement, but none were satisfactory. "They could have scattered prints all throughout the airport," he says. "But they don't work that way; the prints relate to one another."

Even the offered spot where they could have hung together wasn't a good option, he says. That proposal would have the photos tucked away in a tight corner of a lounge, far from main airport traffic. In January, another letter informed Margolis that the photos would be placed in storage. At that point, he elected to have the other five prints placed in storage as well.

"We respected his wishes" in taking down the set of prints, says Michael Giardino, GRIA director of aviation. "We didn't have to; I could have kept it up, and I could put it up tomorrow if I wanted to. But he doesn't want it displayed, and we complied with his requests. We tried to work on a location, but just didn't come to a satisfactory conclusion."

While a major factor in the art supporters' discontent is that the site-specific nature of the work has been brushed aside, they say this is about more than a handful of individual artworks. The bigger picture considers the entire visual impact of the airport — which isn't great — and the sense of place the building projects.

"There's almost nothing in the airport that speaks of what we are," says Roslyn Goldman, who with a few others spearheaded the fight to have the art installed. We could be giving travelers an impression of the Finger Lakes wineries, Garth Fagan Dance, the Eastman School of Music, and our history during the Civil Rights and Suffrage movements, and the Olmsted Parks system, she says.

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Roslyn Goldman.

Rochester is focused on ways to assuage economic decline, says Joni Monroe, an architect and artist involved with the original selection of the airport art. "They're sort of clinging to the dock all of the time. But if this was a more pleasant airport, and it announced the natural and artistic riches of this community, people might come back; it might be a destination."

There's an understandable frustration in their tone when they talk about the airport: they dedicated thousands of hours toward having some sense of the region's culture installed in the first place.

When the airport terminal was redesigned in the late 1980's, the architects factored in space for major works of public art by local artists, which would be paid for as part of the $109 million renovation of the airport ($400,000 was specifically set aside for art). The renovations were funded primarily by the contracted airlines, through fees and rent, and no county dollars went into funding the public art commissions.

Still, there were early signs of opposition from the county: the Legislature approved the first art contract — which allotted $230,000 of that $400,000 for the commissioned pieces — by only one vote.

After a juried competition, two Rochester-based artists were commissioned to create their site-specific designs. Wendell Castle's "Lunar Eclipse" clock tower made of bronze, bubinga wood, and steel was installed in the main concourse just past security in 1992. And Bill Stewart's "The Council," an installation of five 10-foot-tall ceramic figures in a pool, was installed in the east rotunda in 1994.

Round two of commissions had the remaining $170,000 to work with, but the contract would need to be approved first. The projects of four artists were selected from among 27 proposals in November 1991 by an art committee headed by Goldman.

Though the cost of the art was built into the county's contracts with the airlines — a decision made under former Monroe County Executive Tom Frey — the Legislature in December 1991 decided not to take a vote on whether to approve the contract for Phase II of the art commissions.

Monroe County Conservative Party Chairman Tom Cook took up a frankly baffling fight against the art contract. In a Times-Union article from December 6, 1991, Cook said that though the airlines were footing the bill for the art, the fee would be passed on to the public through ticket price hikes — but David Shipley, then USAir VP of public relations, said in a follow-up Democrat and Chronicle editorial that the cost of airport art has "no measurable impact" on ticket prices. Shipley also noted that Rochester was the only community that has tried to block airport art.

To put this in perspective, $170,000 for the remaining artworks would have amounted to less than one-sixth of one percent of the airport's renovation costs — the original $400,000 was already much less than the typical one percent of construction costs mandated for art by ordinances in other cities and counties.

Cook came under criticism when he said the airport art issue would be one key vote that his party would evaluate when making endorsements for the following year's election — when all 29 Legislature seats were up for vote.

"The Conservative endorsement can be especially important for suburban Democrats, who often face uphill battles in the GOP-dominated suburbs," wrote Blair Claflin in a Times-Union article dated December 18, 1991. A D&C piece reported that Legislator Irene Gossin, who did not seek re-election, used her farewell speech to compare Cook to Hitler and US Senator Jesse Helms, who were notorious for their anti-art stances.

City Newspaper reached out to Cook for this article to ask for his reflections on the time period. He says he doesn't recall claiming that the art costs would have an effect on ticket prices.

"That seems kind of bizarre to me," he says. The controversy took place about 25 years ago, and Cook has seen many matters in his tenure that he's regarded as more pressing than the art. He remembers the issue differently, and says his party was concerned that funds for the artists were coming from the public.

"I don't think it's an important issue," Cook says. "Common sense would say, if I'm going to fly to New York City, I'm not going to go half an hour early so I can look at Wendell Castle's something. The general person in Monroe County doesn't go to the airport to look at art."

Before the Phase II vote, Democratic Legislator Frederick Amato of the public works committee said he was uncertain if he would support the contract, expressing caution about adding financial pressure on airlines in a time when some of them were going out of business. This sentiment was echoed by others who said that if airlines went bankrupt, the county would be stuck with the bill.

But it's not like the airlines were going to be saving the money that wasn't spent on art — in a newsletter released by the Monroe County Conservative Party called "Cook's Comments," the chairman said that the money could be put to more utilitarian use, for additional security screening devices, more lounge seating, and more parking space.

Cook said he wasn't opposed to the presence of art in the airport, and proposed a revolving display of amateur work, an idea echoed by the Monroe County Executive-elect, Bob King, who suggested a rotation of work by area high school and college students.

- Photograph courtesy of Richard Margolis

- Wendell Castel's "Lunar Eclipse" was installed in 1992 and removed in 2005.

Goldman and others criticized this idea as parochial, and said that it was counter to the goal of representing the best of Rochester's culture.

An editorial in Rochester Business Journal recommended that the contracts be approved, and people wrote loads of letters to various publications in support of the art.

Despite lobbying efforts by art advocates, the Legislature's decline to vote negated the contract.

The art advocates didn't relent: they shifted their focus to funding, and spent 18 months gathering donations from private donors. An anonymous benefactor pledged half of the necessary funds early on, and after two years, the group raised $186,000 to fund the art, which was then gifted to the airport.

Peter McGrain's "The Monument," a shimmering, nearly 100-foot work of vivid dichroic glass, was installed in a wall of the observation area in 1992. In 1994, Margolis's "Rochester Landmarks Photographs" were installed in the lower level of the terminal. Nancy Jurs' monumental ceramic sculpture, "Triad: Gateway to Rochester," was erected in the Concourse B rotunda. And Ruth Manning's "Bus Transfer by the Dixie Wig" tapestry, made of hand-dyed yarns and depicting a metro Rochester scene, was installed on a wall in the lower level.

A fifth commission was added in 1995: Susan Ferrari Rowley's "Airborne Stabile," a steel and handmade fiber sculpture, was installed in the stairway of the parking garage.

Today, only two of the seven commissions remain, the rest removed in waves of reconstruction and encroaching advertisements.

- PHOTO BY MARY ANNA TOWLER

- An air traffic control tower that was used at the airport until 1949,now installed in the main concourse.

In 2005 — a little more than a decade after the first wave of airport art was installed — the hard-won artwork greeting travelers began vanishing.

Castle's "Lunar Eclipse" was removed during renovations that included a larger screening area to meet increased security measures after September 11, 2001.

"9/11 changed everything around here," says Michael Giardino. There are TSA-mandated elements that are out of administration's control. In particular, changes to security altered the entire center of the terminal building dramatically, he says.

David Damelio, who was acting airport director at the time, indicated that Castle's work would be reinstalled close to its original spot after renovations were finished — and in fact, claimed that even more art, including a newly acquired Ramon Santiago painting, would be displayed at the airport. Damelio was later fired for misuse of funds.

But in 2008, Castle's piece was replaced by the "Clock of Nations" from the recently closed Midtown Plaza. This was meant to be a temporary stay; the Midtown clock was supposed to be relocated to the Golisano Children's Hospital in 2012, but hospital officials decided not to take it. Castle's clock remains in storage.

When asked if there were plans for the clock to return to its place — which would mean relocating the Midtown clock — airport representatives got defensive. The art is the property of the Monroe County Airport Authority, Giardino says. "These were commissioned pieces that the artists were paid for." The contracts gifted the art to the airport, "and according to the contracts, the Authority has the right to do what it wants."

Nancy Jurs was caught by surprise in 2006, when she met with airport officials to discuss restoring the worn platform of her sculptures. She was instead informed that her sculpture was to be removed to make room for a larger business center, to replace the small one previously located near the food court.

The new Frontier Communications facility — which came after a survey by the airport found that 65 percent of its travelers were business people — is enclosed by a large frosted-glass circle.

Jurs was offered an alternative site for her work: outside, between the parking garage and Brooks Avenue. But because the sculptures couldn't withstand the Rochester weather, Jurs offered to redesign them for an outdoor site, but she says she wasn't enthusiastic with the placement offer.

"They were made to be a gathering center," Jurs says, "specifically designed for the rotunda."

Jurs says that about five years ago, the airport director at the time, Susan Walsh, was ready to give Jurs' work back to her, so that she could install it elsewhere in Rochester. While waiting to hear back from Maggie Brooks, Walsh was arrested for a DWI and removed from her station. Jurs' sculptures remain in storage.

Ruth Manning's tapestry was removed in 2006 for unspecified reasons. Goldman says that she spotted it in the lobby of the airport administration offices, out of public view.

Going by the section on "art and culture exhibits" on the airport's website, an out-of-towner might assume that the commissioned works are still displayed in the airport. They'd find a different picture upon arrival.

There are abundant advertisements for the University of Rochester, jewelry, and car dealerships; there's a display center showcasing a collection of US Presidential Letters; old-timey airplanes suspended from above; and some of the 119 regrettable "Benches on Parade" — which was a great charitable cause, but the medium is an eyesore and much of the art forgettable.

McGrain's window remains, and will probably stay. "They can't sell that space," Margolis says.

The art is important to the Airport Authority, Giardino says. "But we strike a balance, because we have to pay for the airport as well. We have not only federal mandates, but we are an independent authority and no tax dollars go into running this place."

The primary source of revenue is the airlines themselves, but that's only 50 percent of what it takes to operate the airport, he says. The other sources, called "non-aeronautical revenue," include revenue from parking, advertising, concessions, and other leasing and rents.

GRIA is a "cultural place, but it's also touted as an economic driver, and has an economic impact," Giardino says. "When an advertiser — a local advertiser especially — is coming into the building and we've had two of the major employers in this county advertising, I think it also displays the economic viability of the area. But it's a balance. I think they're both important, but one just happens to generate revenue, which pays for utilities, salaries, and equipment, and the operations here." That keeps "the costs low for the airlines, and hopefully keeps the costs low for the traveling public."

Airport representatives argue that the ads boost local businesses, but this seems to create a false dichotomy between art and business. Art is also an industry. The airport art serves not only as an advertisement for our region's rich culture of working artists, but also for the individual artists' small businesses. And when they get work, money goes to the firms that supply their materials, to contractors who help with creation and installation, and so on.

"I don't mean that the budget is unimportant," Margolis says. But it's also important to consider the value that the impression of art in the airport makes.

Elsewhere, airport art collections aren't treated as a minor concern. Many of the collections were grown from money mandated by "percent for art" laws, under which anywhere from one-half to one-and-a-half percent of every public construction budget must be set aside to purchase art. Depending on the size of the project, this frees up sums for art that can rival museum acquisition funding.

In 1991, when Rochester was in the middle of its battle over airport art contracts, the new Denver International Airport, which opened in 1993, had $6.5 million set aside of the original $2.3 billion construction cost for purchasing sculptures, murals, and installations, and now boasts one of the most extensive airport art programs in the world.

There are numerous examples, nationally and internationally: Albuquerque International Airport showcases New Mexico's contemporary art and traditional crafts with a display of 93 pieces by 82 state artists; Anchorage International Airport (which serves only about 2 million more passengers annually than GRIA does) has 100 Alaskan Native artworks on display; and San Francisco International Airport not only has a permanent collection, but an exhibition series. Similar programs can be found in the airports of Seattle, Phoenix, and Las Vegas.

But not every airport art collection is funded by construction projects. Chicago's O'Hare International Airport is filled with murals, sculptures, paintings, and exhibits, which are all supported by Chicago's world-renowned Public Art Program, which exhibits several hundreds of works of art in more than 150 municipal facilities around the city, such as police stations, libraries, and CTA stations.

The second point on Margolis's petition calls for the formation of such a public art program, with a similar vision for more than the airport environment. This committee could not only coordinate funding for an exhibition series at the airport, Goldman says, but also direct money for maintenance and conservation programs for the permanent art collection, and oversee public art installations elsewhere in Rochester.

The argument can be made that some of these other airports are larger than GRIA — Denver International serves about 50 million passengers annually to GRIA's roughly 2.5 million — and have more resources that can be dedicated to funding art. We've had challenges getting the art funded, sure, but the biggest challenge seems to be locating spaces for the already available art that make both the airport and the artists happy.

The petition also appeals to the office of County Executive Cheryl Dinolfo for support in these issues. The county's webpage lauds the community of artists that partially defines this region. City Newspaper contacted Dinolfo's office for a statement, but did not receive a response.

After the short-sighted destruction of Rochester's beautiful Claude Bragdon-designed train station in the 1960's — that was replaced with a seriously diminished version — the airport has been the principal gateway that could give travelers a sense of the local culture. Many business and community leaders promote Rochester as an arts city, part of an arts-rich region.

One more potential hiccup on the horizon is that the actual structure of the airport may change again in the coming years. Governor Andrew Cuomo's administration announced in January a $200 million Upstate competition to revitalize the region's airports. If selected, the Rochester airport could undergo structural changes once more.