Sorrow and angry grief smacked my brain when I saw the work in the addiction-themed group show currently up at AXOM Gallery. This past summer, when I was moving the last of my belongings into the house I currently live in, I paused setting things up to gather around a backyard fire with my new housemates. The sun had long since set, and more people were showing up to be together while we mourned our friend Max, who had overdosed and died a few weeks prior.

"Sorry your move-in party is a memorial," one housemate told me with a sad snort.

We passed mugs of tea around, sharing stories about our dead activist friend, who was hungry to help others, who would have given anyone his shirt or shoes and was planning to travel to Syria to support the grassroots defense against ISIS. The unspoken truth was that carrying so much care for the world was probably what sank him.

I've known three young people whose addiction has killed them in the last five years, and I've recently become aware of several other friends who use or did in the past. Nearly everyone I've talked with about the issue has lost someone or fears they're going to.

At a second memorial held later in the summer, some of Max's friends organized an opportunity for anyone who wanted to become certified to administer Naloxone to get the training.

"NARTCAN," at AXOM, was put together by Justin Chaize, a registered nurse and a grad student at the UR School of Nursing's Family Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner Program. He's specialized in mental health and addictions for 10 years, a result of genuine empathy.

"I have struggled with periods of anxiety, depression, and addiction in my life," he says. "There is a need for this type of work. I noticed a lot of people in recovery practice and appreciate the arts."

Chaize began planning the exhibit more than a year ago, and put out an open call for art through the New York Foundation for the Arts website. He received submissions of work from artists based in New York City, Toronto, the Boston and Cape Cod area, Chicago, and Rochester.

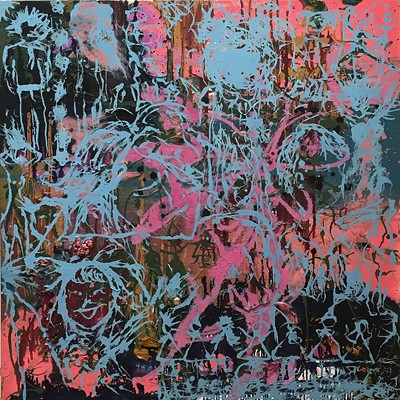

"NARTCAN" is a collection of therapeutic responses to addiction by addicted artists as well as contemplative work made to commemorate those who got lost in their dips into oblivion. The responses that Chaize received run an incomplete gamut of addiction issues; most of the images and stories are of white people who are afflicted or affected.

Justin Sterling's oil-on-glass "Self Portrait" shows the artist grimacing immediately after taking a pull from a cigarette. Other works focus on the general impact of addition (isolation, fear) rather than a specific substance, but both the show title and many specific works point directly to the opioid epidemic.

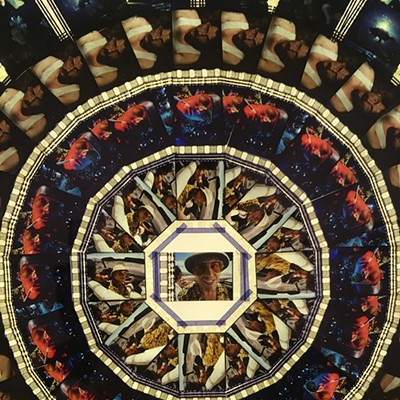

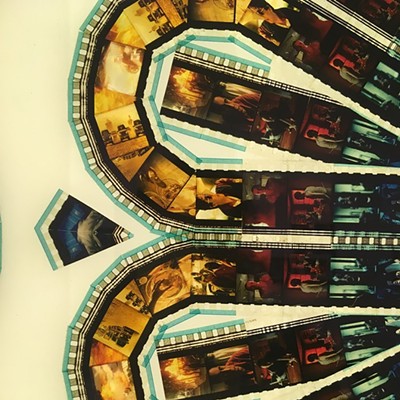

Raymond Waters' "Transformation" is made of colorful 35mm film from "Trainspotting," "Traffic," and "Requiem for a Dream" arranged into stained glass-like florets on back-lit Plexiglas.

On the back wall, two starkly different black and white pictures of heroin addicts are placed side-by-side: Claire Martin's "Tony," who Martin photographed in his cramped hovel as he bent his lean, Iggy Pop-like, ravaged frame over a forkful of pie; and Antonio Barbagallo's more formal, gentler portrait of Rochester's own Philip Seymour Hoffman.

"Those images are so opposite," says artist and AXOM co-owner Rick Muto. "We have a beloved actor, very talented man, that's what we remember, except we know he died of an overdose. Inside, strip away the veneer, they're the same person, they're a person struggling with addiction. Hoffman was lucky enough to be in recovery for 20 years, but still, it got him."

Muto says that one of the reasons he agreed to host the show was the series of photographs and story of Josh — a young man who died of a fentanyl OD — submitted by his mother, Susan Carr. The gutting first sentence of her essay reads: "Josh began using heroin at 15 his bio dad gave him the drugs."

The exhibit aims to humanize the abstract concept of drug addiction, Muto says. "Here's a condition that we know exists intellectually, we know it exists statistically, but do we really know it exists from a humanistic point of view? Or what it's like, unless we've had a friend or relative who's been afflicted with this?"

A percentage of the proceeds from the show will be donated to the construction of The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Sisters of Charity Hospital in Buffalo. Save a life: Trillium Health offers FREE ongoing opioid overdose prevention trainings to the public: info at trilliumhealth.org.