The exhibit of David Levinthal's photographic works at the George Eastman Museum, "War, Myth, Desire," follows the museum's 2014 showing of monumental photos from his "History" series. This current exhibit is a retrospective, created with the intention of both highlighting the recent major acquisition of Levinthal's works by the museum and also exploring the overarching themes present throughout his 40-year career. Levinthal chose the title "War, Myth, Desire"to also reflect some defining and enduring themes of the human experience. While the exhibit showcases his photographs of toys, the framing of the work calls into question what Levinthal has to say about his chosen themes.

Dozens of Levinthal's images from several of his major series are presented in the museum's Main Galleries without an artist's statement and with minimal curatorial commentary. This avoids giving viewers an overt directive and narrative while it allows individual viewers' reaction to the images to become the central part of the exhibit, rather than the images themselves. Throughout the show, staged and photographed army men, Barbie dolls, and other intricate figurines are used to explore some of the basest parts of American history and popular culture, presented from the perspective of the white male gaze. The audience is challenged to decide: are the works critiquing or reiterating these themes? Are they deconstructing or reinforcing stereotypes?

Icons scattered through the exhibition space alert viewers to an accompanying podcast that can be accessed online or over the phone, in which carefully selected questions are posed to a bevy of experts in visual and social fields. Aside from this resource the museum is also offering some upcoming related programs including two curator's gallery talks this summer and winter and an artist's talk on November 1.

- PHOTO COURTESY GEORGE EASTMAN MUSEUM

- Untitled 1989 image from David Levinthal's "Wild West" series of photographs.

If the themes of war, myth, and desire provide a construct for the exhibition, the presence of large Polaroids and larger inkjet prints that are saturated with color dictate the show's direction. Though the first room is filled with Levinthal's earlier works, which are smaller in scale and more subtle in their color than his later and most recent works, a large inkjet from his "History" series is positioned as the first and most dominant image at the entrance of the space. This introductory image, titled "The Searchers," features a lone, masculine figurine in blue jeans, a red shirt, and a dark cowboy hat, with a rifle held by the barrel and slung across the shoulder of the toy.

A narrow depth of field is used to give the illusion that the figure is staring off into a distant sunset. The only other figure in the image is a skull; possibly that of a steer. This masculine conqueror who looks out onto land which is or could become his is a recurring character in Levinthal's work. Not that he is physically present in each image, but his brash and bold survey, exploration, and ownership of all before him can be felt in each of the images throughout the themes of war, myth, and desire.

The topics of desire and war feature heavily in Levinthal's earliest works, displayed in the first room of the exhibition. The small scale, subtle colors, and salon-style hanging of the works invite the viewer in for closer examination. In the groupings of "Bad Barbie," "Modern Romance," and "Porno," Levinthal positions the viewer as voyeur, a peeping tom that must lean in to see what the dolls are doing. Despite not having genitalia of their own, the figures positioned to imply sexual activity or heightened sexual tension.

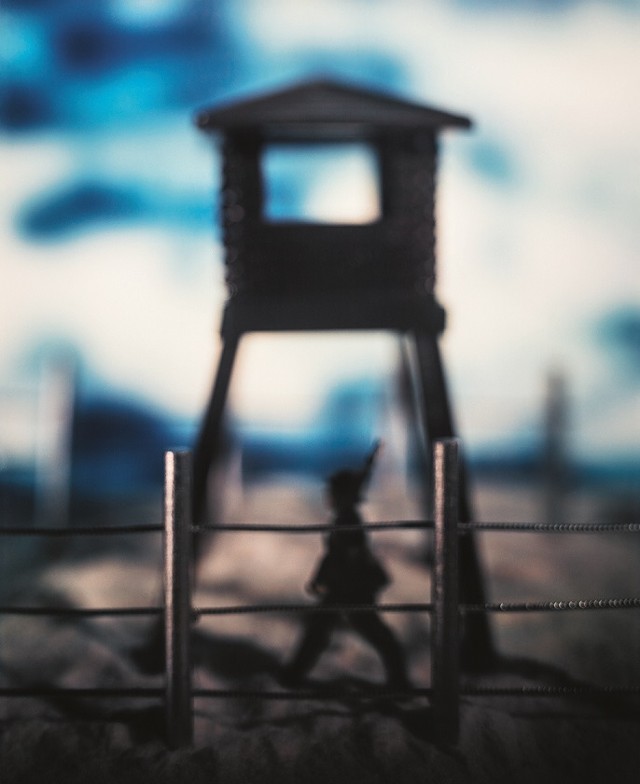

While many of Levinthal's photographic skills were developed during the Vietnam War, the war images that are side-by-side are from his "Wild West" and his "Mein Kampf" series.Simulated battles are present throughout the works, but the literal wars represented were not contemporary to Levinthal. Instead, the war photographs look back through nostalgic lenses, the heroes and bad guys clearly defined.

- PHOTO COURTESY GEORGE EASTMAN MUSEUM

- Untitled 1994 image from Levinthal's "Mein Kampf" series of photographs.

"Wild West" contains some of the few images of brown people in the show, but they represent characters instead of people, and play into shallow pop culture tropes of Native Americans. Armed and on horseback, the figures are central to the photos, and Levinthal played with focus and depth of field to create a sense of motion, rushing, and urgency. They seem to gallop past the viewer, moving horizontally across the image as if into the next photograph or across a television screen.

The cowboys in this series are presented as heroic rescuers; taming a horse or riding directly toward the viewer and into action that could be happening on the museum floor. In her remarks during the exhibit's opening, the museum's Curator in Charge for the Department of Photography Lisa Hostetler said that our national identity was strongly shaped by the ubiquitous presence of the West in film and popular culture during the 1950s and 1960s. She claims that because of the way Levinthal photographed the toys, viewers are given space to consider the viewpoint of both the cowboy and the indigenous people of the West.

On the surface, the "Wild West" images are not about the atrocities committed upon Native Americans but celebrate the lone cowboy, rushing from the image to rescue the viewer from the unseen surrounding hordes of natives. The work explores the American myth of the heroic cowboy who is credited for taming a people and a terrain. But where it could have built a narrative that recognizes the accomplishments, sovereignty, and humanity of indigenous peoples prior to the arrival of American colonizers, the series merges war and mythology and relies on its audience to determine the difference between nostalgia and criticism of an American West that never was, but that dominated popular culture for a generation.

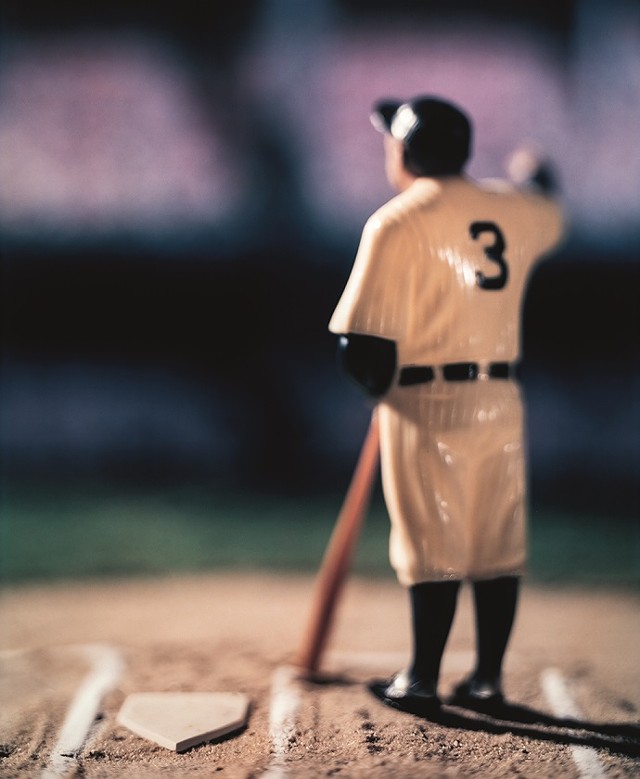

- PHOTO COURTESY GEORGE EASTMAN MUSEUM

- Untitled 2003 image from David Levinthal's "Baseball" series of photographs.

Circling the room counter-clockwise, viewers next encounter images of sports and athleticism in a section labeled "Baseball and Hockey." Though they echo the war images' evocations of heroism and action, the sports figurines are shown with less environment and background than the images that directly reference war. Many are also lacking the depth of field technique used to imply motion, action, chaos, and destruction shown in the war images.

Combined, these techniques make the sports images feel similar to the ones in the next suite of images labeled "Desire," but they are different from the images of feminine figurines in how their lighting and framing highlight the toys like heroic champions and instead of anonymous objects of the male gaze.

- PHOTO COURTESY GEORGE EASTMAN MUSEUM

- Untitled 2001 image from Levinthal's "XXX" series of photographs.

Again viewers are left to decide if the images are purely representations of nostalgia, or if they reflect a culture that holds battle and toxic masculinity in such high regard that athletes become the subject of a twisted hero-worship.

Interestingly, the sports section has one of the only toys representing a person of color without the negative tropes, stereotypes, and one-sided nostalgia associated with the other brown and black people featured through the exhibit: A single central figure, lit dramatically, and framed and treated similarly to the other sports figures. But it's the only sports figurine without the hazy background environment implying a stadium, audience, and outside action.

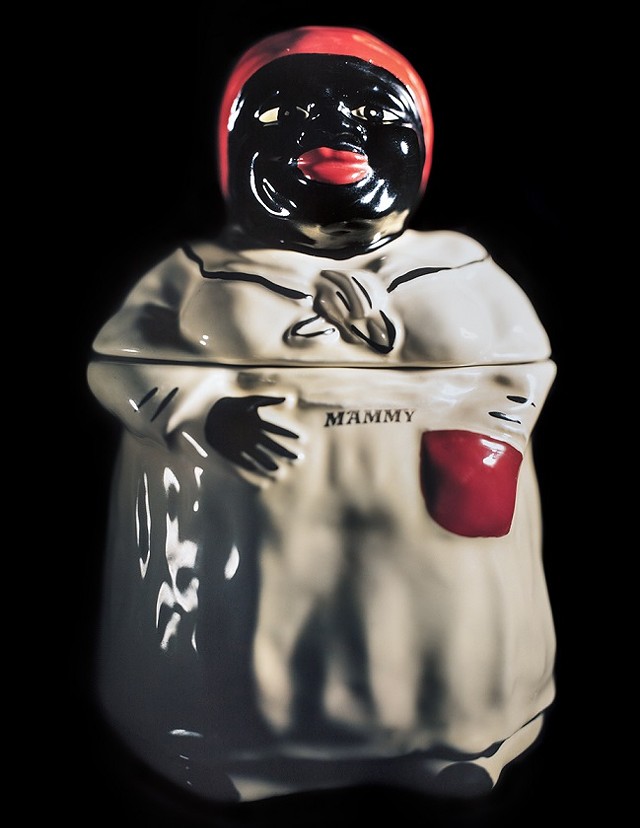

The figures, tchotchkes, and racist memorabilia in Levinthal's "Blackface" series are also presented without hint of environment -- they're posed in front of a dark background, and lit in a way that highlights their colors and exaggerated expressions.Curatorial information states that the series is intended to highlight the insidious and pervasive nature of the toys, advertising, and household goods that depicted caricatures of black people. But their placement, between Levinthal's "Passion" and "Space" series, has them flanked by themes of sexuality and mythology. It was jarring to see this propaganda -- a tool of warfare used against black bodies in America for centuries -- positioned with the mythos of the hypersexualized white woman and of the Space Race instead of the images of war. These objects are not a source of warm nostalgia for many viewers.

There are few legible words within any image in the exhibit, and for the most part those that are clearly legible serve to create atmosphere or give the images a sense of place and environment. A notable exception is the first blackface image seen straight-on when turning right and walking into the second gallery space. The word "mammy," a word used for generations to diminish black women, is visible on a lidded jar shaped like a plump figure.

- PHOTO COURTESY GEORGE EASTMAN MUSEUM

- Untitled 1995 image from David Levinthal's "Blackface" series of photographs.

During his exhibition preview talk, Levinthal discussed how the "Blackface" Polaroids aim to monumentalize the objects and confront the audience with the nature of their intended purpose. But it's unclear how the images and their placement in the exhibition contribute to the conversation of race and identity in America in a constructive way, or if they sustain the new popular narrative that the destructive representation of people of color in popular culture is a thing of the past, like the Space Race. Are racist depictions of black people a titillating and tantalizing experience, like the "Desire" images?

And during an interview with Levinthal after the exhibit walk-through, he admitted his work is informed only by his own limited experience and lens, which has clearly influenced his understanding of the role of popular culture on the American psyche. He says many of the images he created because of his fascination and curiosity around the figurines he collected -- in his career he's examined multitudes of objects created for a white audience. While he recognizes that everyone brings their own personal and cultural history when viewing a work of art, Levinthal hopes that the work both entices and confronts audiences. Both Levinthal and Hostetler expressed a hope that the viewers reflect on and discuss not just the emotions that the exhibit may evoke, but the source of those emotions.

Levinthal does not moralize in his work, and the exhibit's presentation allows viewers to come to their own conclusions about what ideas are being presented. But without the guidance of the podcast or the curators walkthrough, the audience might struggle to reach the conclusions intended by the museum and the artist.